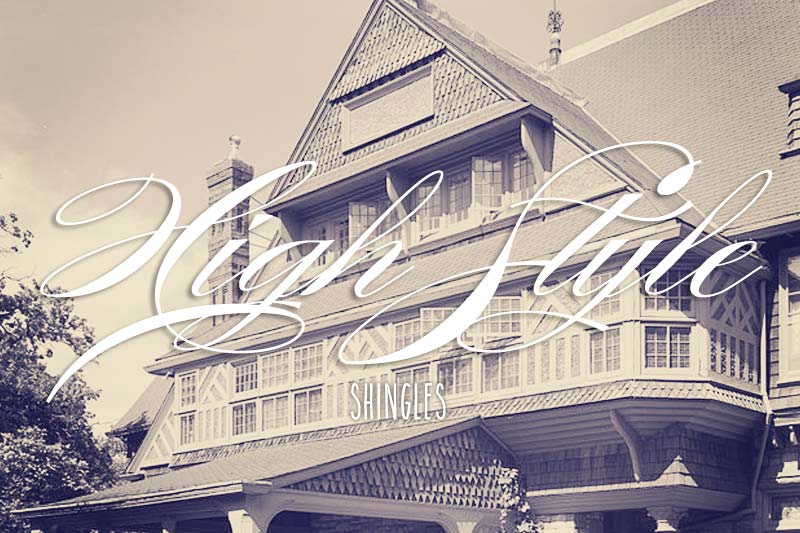

by Hänsel Hernández-Navarro (photo by WindingRoad)

If there’s one thing we love about CIRCA, it’s the chance to “tour” the great vernacular architecture that makes America wonderful. Love shingles? You’re most certainly not alone! Join Hänsel as he teaches us all about the Shingle style.

The Shingle Style 1880 – 1900

The Shingle Style originated in New England in the 1880s and and became popular across the whole of the United States by the beginning of the next decade, the 1890s. Like the Richardsonian Romanesque and the Queen Anne, it is a genuine American vernacular style of the late 19th-century. It was historian Vincent Scully who in the 1950s identified and named this style, which appears to be a reaction to the excesses of the Victorian and the Queen Anne Styles. The Shingle Style avoided fussy effects and complex wall surfaces and textures in favor of a uniform wall covering of wood shingles, reducing and distilling them to bare essentials and forms like our early colonial houses. The style was an early manifestation of a ‘colonial revival architecture’ that emulated the New England salt-box and other colonial houses’ plain, shingled surfaces as well as their massing.

Oliver T. Sherwood House, Southport Connecticut.

Most peculiarly, the style culminated in a short period of time: twenty years, from 1880 to 1900, and reached its highest expression in the rambling seaside estates and resorts of the New England coast like Newport, Cape Cod, eastern Long Island; and also coastal Maine had numerous architect-designed cottages in the style, many of which survive today. Also known as ‘seaside style’, the Shingle style is not that common outside New England and never gained the wide popularity of its contemporary, the Queen Anne style. But since it started among the higher and fashionable social circles, it was well publicized in contemporary architectural magazines. The style spread throughout the country on a limited basis, and scattered examples are found today in most areas of the country.

Henry Hobson Richardson is credited with designing and building the first Shingle house prototype, the Sherman House of Newport, Rhode Island in 1876.

What Makes a Shingle?

/

The Shingle style rejects excessive decoration and embellishment and seeks instead the effect of a complex shape enclosed within a smooth (wood shingle) surface. It is the wall of shingles which unifies the irregular outline of the house. In Shingle style houses decorative detailing, when present, is used sparingly. The style emphasizes the volumetric spaces within the house more so than exterior surface details.

In Shingle style houses the walls appear as thin, light membranes shaped by the space they enclosed. The effect is heightened by bulging segmental bays or half round turrets jutting out from the body of the houses rather than as fully developed elements. At times the shingled walls seem thinner and lighter when contrasted with a basement floor of rubble masonry or fieldstone.

Roofs are usually of gentle pitch with extensive gables; in two-story houses the roofs even go down and out to the ground-floor level harking back to lean-tos found in 17th century New England saltbox houses. The gambrel roof is more common than the hipped. Chimneys are generally less obstrusive, conforming to the prevailing horizontality of the Shingle house.

The Shingle style does borrows some features from the Queen Anne style: wide porches, shingled surfaces, and asymmetrical forms. But the architects who designed the Shingle, favored opening up the interior space but with few rooms. The rooms, however, were a lot bigger in size making sunlight easier to reach in and light the interior.

Style’s Identifying Features

• Houses are generally two or three stories tall

• House spreads low and anchors to ground on a heavy stone foundation

• Weight, density, and permanence are emphasized and articulated

• Dark and rough-hewn stone masonry

• Asymmetrical volumes in the form of cross gables and roof sections of different pitch, wings, turrets, bays, and oriels

• Shingles in many colors, such as the Indian reds, olive greens and deep yellows

• Shingles form a continuous and contoured covering, stretching over roof lines and around corners

• Sweep of the roof may continue to the first floor level providing cover for porches, or is steeply pitched and multi-planed

• Entries defined by heavy (often low) arches

• Columns are short and stubby

• Wide porches

• Broad gables

• Small casement and sash windows which may have many lights, and often are grouped into twos or threes

• An “eyebrow” dormer is distinctive

• Free-flowing interior

• Large rooms and porches loosely arranged around an open “great hall,” dominated by a grand staircase.

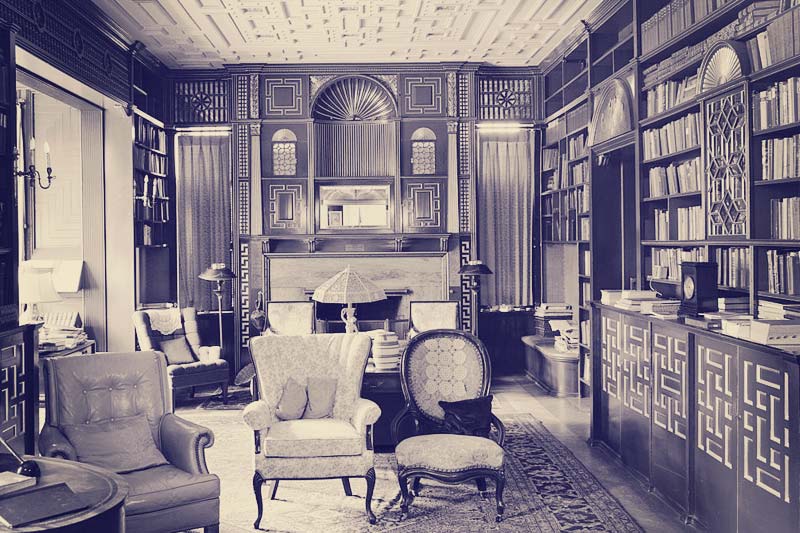

Shingle Style Interiors

Freedom and openness characterize the Shingle style interior. The focal point is a living hall complete with fireplace, which is a feature inherited from the English Queen Anne houses. The main stairs often rise from the living hall, around which one finds other reception rooms. These rooms are often entered through wide openings with sliding doors, so that the whole area could be made into a single, subdivided space. Verandas and porches are integral parts of the plan not attached as in Romanesque or Queen Anne houses.

Wood paneling predominates in the main rooms. In fine houses it might be raised-panel mahogany to the ceiling, oak in other houses, and in more modest seaside Shingle cottages, battens or beadboard paneling.

John G. Richardson-Sophia E. Blatchford House, Newport Rhode Island.

Parlors might be done in European or Aesthetic Movement styles, but also ubiquitous to Shingle style is a predilection for formal Colonial Revival dining rooms.

The Shingle style, unlike the earlier Victorian aesthetics which preceded it, was an unusually free-form and variable style. One reason for the range in variety is the that it had originated and remained primarily a high-fashion style designed by architects for the wealthy rather than becoming, like the Queen Anne, adapted for housing among all social classes of Americans.

Among the architects working in the style were Henry Hobson Richardson, William Ralph Emerson of Boston; John Calvin Stevens of Portland, Maine; McKim, Meade, and White, Bruce Price, and Lamb and Rich of New York; Wilson Eyre of Philadelphia; and Willis Polk of San Francisco.

Samuel Tilton House, Newport Rhode Island.

AUTHOR HÄNSEL HERNÁNDEZ-NAVARRO

AUTHOR HÄNSEL HERNÁNDEZ-NAVARRO

Hänsel Hernández-Navarro is an architectural conservator specializing in the preservation and rehabilitation of historic buildings and monuments, and cultural resource management. He received his Masters in Historic Preservation from Columbia University. He lives in New York City and has worked for the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, the Getty Conservation Institute, the National Park Service, The American Academy in Rome, and the Museum of the City of New York.